Is psychological disability in Sweden really stopping so many from working?

(Update from June 2013: This post is actually about the pathologising of human experience: how more and more people are being labelled as ‘disordered’ or ‘deficient’ by the psychiatric profession in Sweden and the expectation that individuals fit with certain norms of behaviour. Some bloggers have attempted to use my words as evidence that Sweden is suffering from collective mental breakdown due to a breakdown of gender expectations and norms. I am certainly NOT suggesting that. If anything, taking a more gender neutral approach in education and other social functions has contributed to greater personal freedom for Swedes. However there is an increasing requirement for individuals to be diagnosed with an illness or disability in order to access support. Read on for more…)

The Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter has run a story about the sharp increase in numbers of young people leaving work and put onto disability pensions (known as ‘activity support’ for those under 30 and ‘sickness benefits’ for those 30-64).

Fewer young people are returning to employment after being pensioned off work, a phenomenon that has been referred to as a ‘ticking time bomb’ in view of the fact that many may be destitute by the time they are 30.

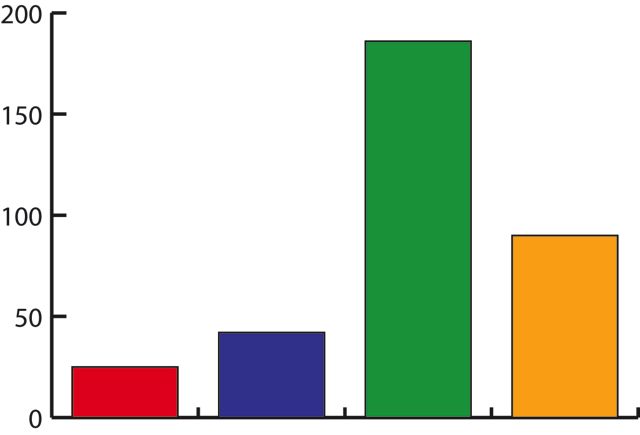

Sweden is not alone here. There were increases in young people starting on disability support in other Scandinavian OECD countries between 1995 and 2007. In Finland the increase was 5 percent, in Denmark 10 percent but Sweden had a massive 80 percent increase! That’s almost 30,000 people under 30 in Sweden who are on a disability pension.

Psychiatric Disorders Becoming More Common in Sweden

So why the huge increase? Well 73% of those young people have been given medical psychiatric diagnoses such as autism, ADHD and Aspergers. Could it really be that Sweden had such a rise in psychiatric disorders and mental disabilities compared to our Nordic neighbours? Is it something in the water?

As a counsellor, therapist and coach, I am often asked about such diagnoses and the increases. I think people expect me to say something about teenage computer gaming culture or genetics or to applaud the ‘science’ responsible for discovering such a vast previously undiagnosed population.

But what I see happening in Sweden is that so-called ‘normal’ behaviour is becoming more defined. The goal posts for what is considered normal are being brought closer together. The tolerance for non-conformity and extremes of mood and behaviour is reducing. It is becoming harder to be ‘lagom’!

In Sweden, psychiatric health has been constructed as a medical problem. Both anxiety and depression are treated primarily with medication. But drugs are also heavily prescribed for those whose attention, communication techniques or social skills fall outside what is measured to be the norm. And unfortunately, those norms are progressively less accommodating.

There’s no doubt that the pathologising of human experience is increasing in many countries. More people are being diagnosed as depressed, anxious, having a mental disability or disordered in some way. And this corresponds to increasing expectations that we fit prescribed ways of being and relating to each other. In workplaces and schools across Australia, the United Kingdom and America, more standards of performance are being established and procedures for selection are becoming more sophisticated.

Fortunately, not all mental health, psychotherapy or counselling practitioners favour responding to diversity with drugs or exclusion and many take a more norm-critical approach. Narrative therapy, Open Dialogue and other collaborative therapeutic practices are approaches which honour what people have to say about their own experience, rather than categorise us using medical terminology.

My hope is that eventually the doctors, psychiatrists, psychologists, therapists and others responsible for measuring, diagnosing and categorising people will see the limitation of these practices. I look forward to a new era when Swedish society ceases to be obsessed with locating its deficits and deficiencies but instead acknowledges the unique skills, competencies and abilities of all individuals. A time when the expertise we bring to life’s challenges is respected and valued by the health professionals we consult and diversity is appreciated rather than shunned. Perhaps then we will see more young people participating in the workforce in Sweden.